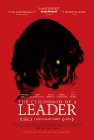

Eye For Film >> Movies >> The Childhood Of A Leader (2015) Film Review

Brady Corbet’s fiercely ambitious and gripping debut is less concerned with straightforward narrative than with mood, building a visceral, terrifying almost tactile picture of the titular child – nameless until virtually the end of the film – through a series of dark vignettes each concerned with a “tantrum”, showing a cycle of temper that increases in severity, or at least in impact, as he ages. The initial outburst is described as The First Tantrum. A Sign Of Things To Come – this is history repeating itself in miniature, but each time on a slightly broader canvas – with the tantrum aspect crucial; these are rages of self-absorption, a violence of vanity, with the ego dominant.

Corbet sets the emotional tone from the start by letting the score by Scott Walker do the heavy lifting. Violins skitter around, mocking the rest of the orchestra during a segment entitled Overture, which sets the action firmly at the end of the First World War, showing battlefields and a train, ploughing on relentlessly, proving that imagery doesn’t have to be subtle to be effective. It also shows Woodrow Wilson and Georges Clemenceau in Paris for the creation of The Treaty of Versailles. Fascism lurks like an undertow, just waiting to suck characters in.

Somewhere in the depths of the French countryside, our boy (Tom Sweet) is living with his parents, first seen, ironically, sporting the wings of an angel for the local nativity play. He may look angelic but this is Little Lord Fauntleroy meets Damien, a carefully positioned character, with Brady refusing to take sides and present him as inherently evil or saintly but whose wilfulness is never in doubt. Sweet is remarkable as the young boy, embracing the ‘seen and not heard’ ethos of the age to a large degree, so that he is as much a victim as villain. An episode of stone throwing and the strict reaction of his mother (Berenice Bejo) brings with it a sense of dread that only builds as the action progresses.

Stress and isolation are everywhere, not just for the child but for the mother, whose American diplomat husband (Liam Cunningham) rules the house with a rod of iron. “One way or another we will force the world to be a better place,” he says, with doctrine and disaster running hand in hand. Enforced doctrine is the devil here, whether it’s coming from the church or closer to home, as we watch the boy begin to flex his Machiavellian tendencies. Almost all the action happens behind the closed doors of the farmhouse, its drab palette of browns and inky blacks adding to the unsettling mood, with cinematographer Lol Crawley moving between the realms of the Old Masters to dizzying camera movements that are intended to disorientate as much as the script. Threats are spoken but also implicit and the cumulative effect on the viewer is tensely hypnotic. After all, what’s so sinister about reading Aesop’s Fables? Everything and nothing, Corbet suggests.

Those sold on seeing the film on Robert Pattinson's presence are likely to be disappointed. His appearance here is crucial narratively but unusually small for an actor of his box office heft. Corbet and his co-writer (and wife) Mona Fastvold are more concerned with big ideas than big names and those who prefer cryptic cinema will not be rewarded in full.

Corbet bears the influence of some of the directors he has worked with – most notably Michael Haneke. But he also draws on more literary Modernist ideas of fragmentation and disillusionment prevalent in the period where the film is set; one early nightmare scene within the halls of power spins up to a skylight in an almost physiological assault of light on our eyes after the darkness of the family’s house and is an unsettling hint of the maelstrom that is to come. By the time we return to that terrifying turbulence, the dread circle is complete, the boy’s name is revealed and the sense of history looping destructively forward seems horrifying in its inevitability.

Reviewed on: 16 Aug 2016